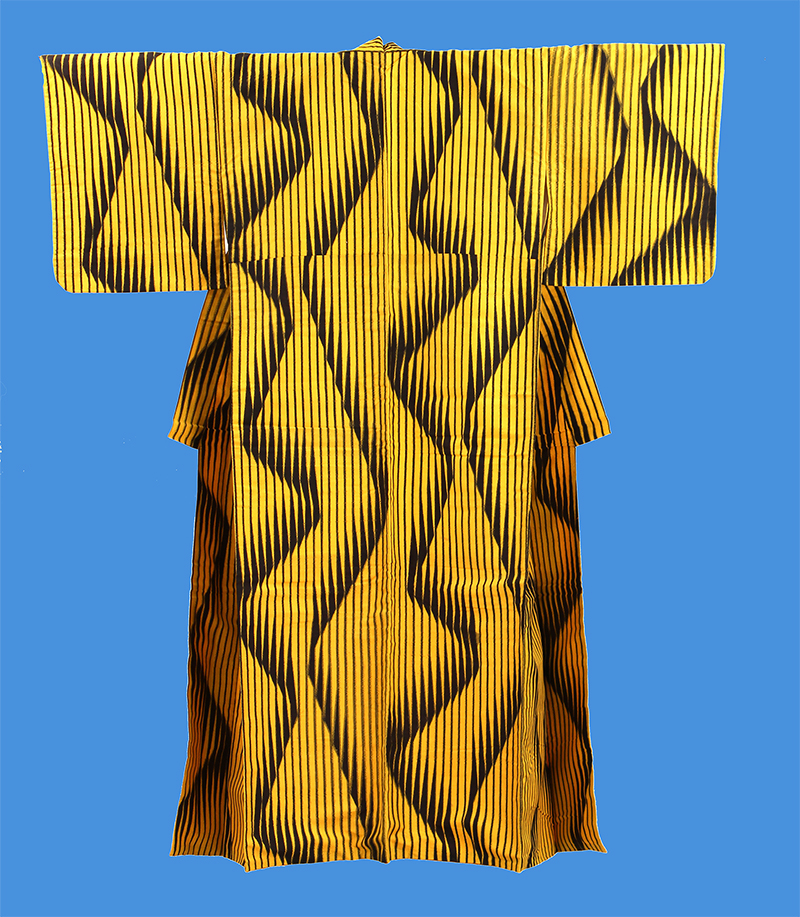

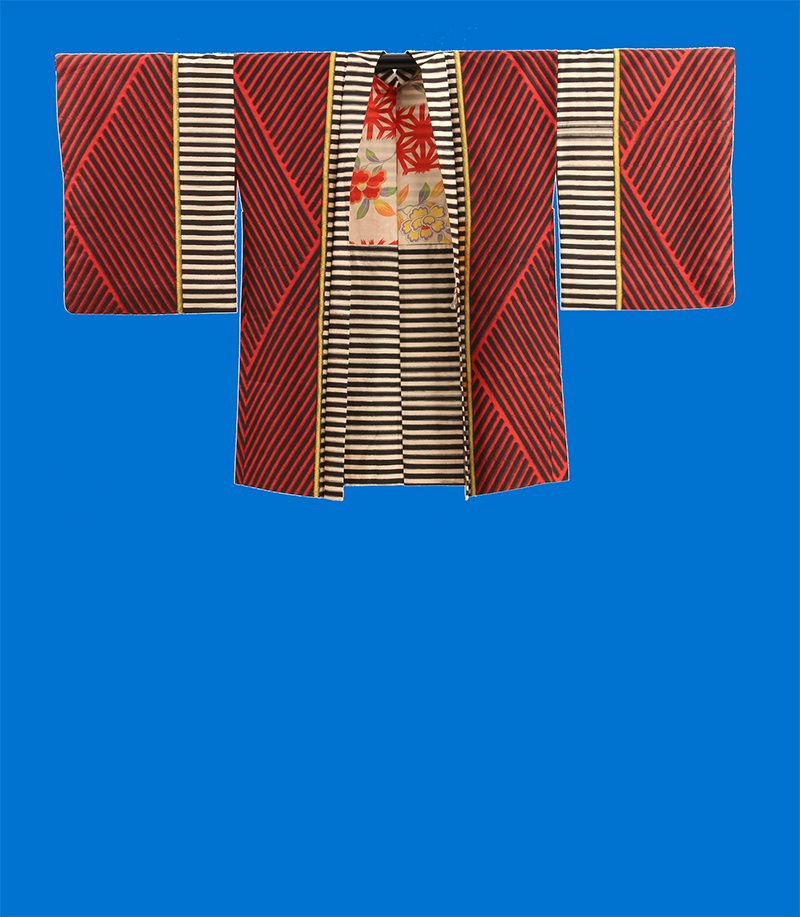

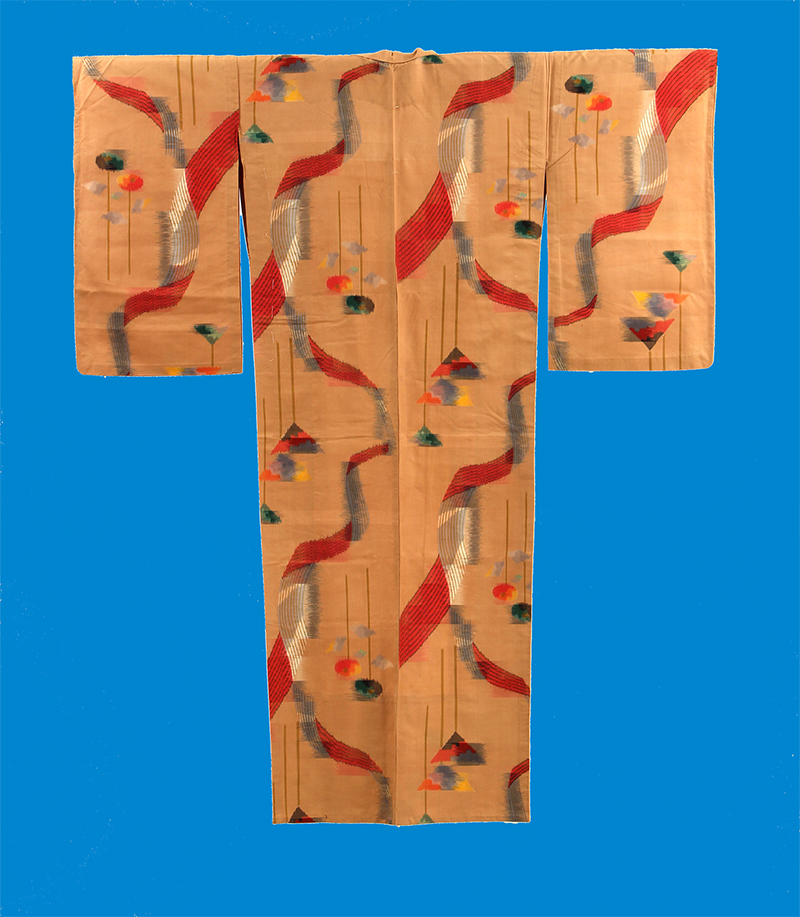

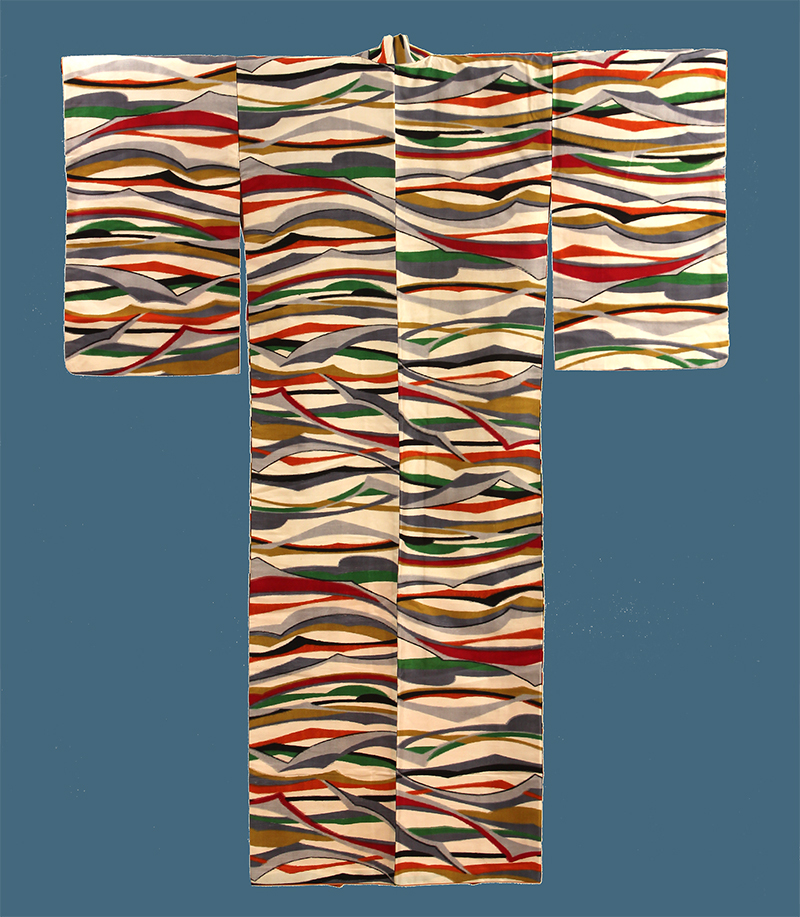

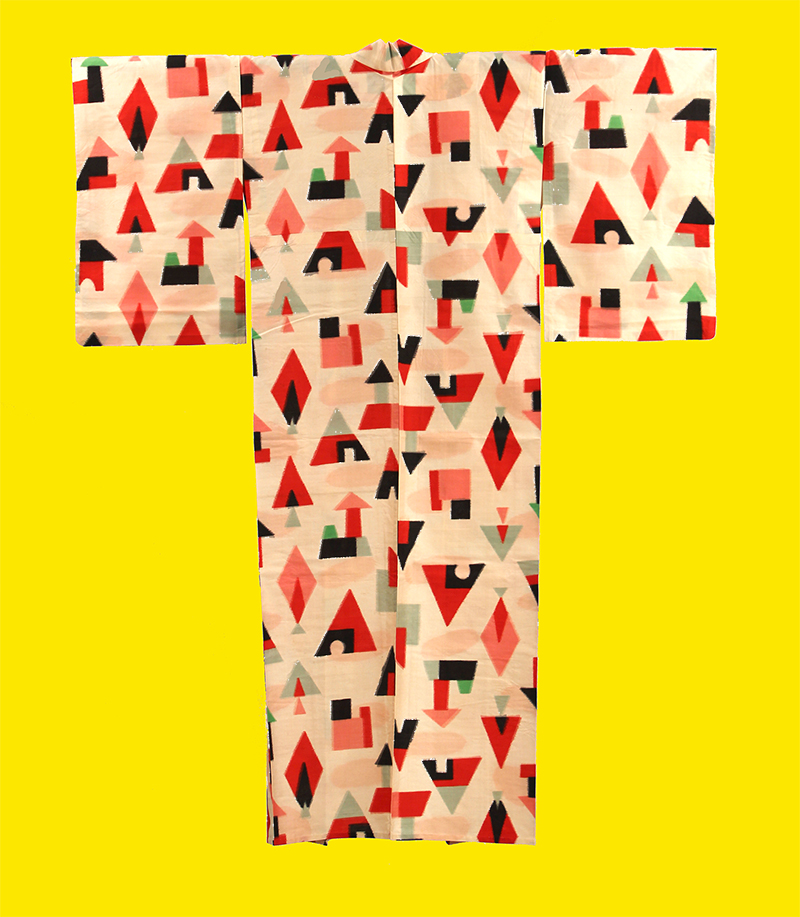

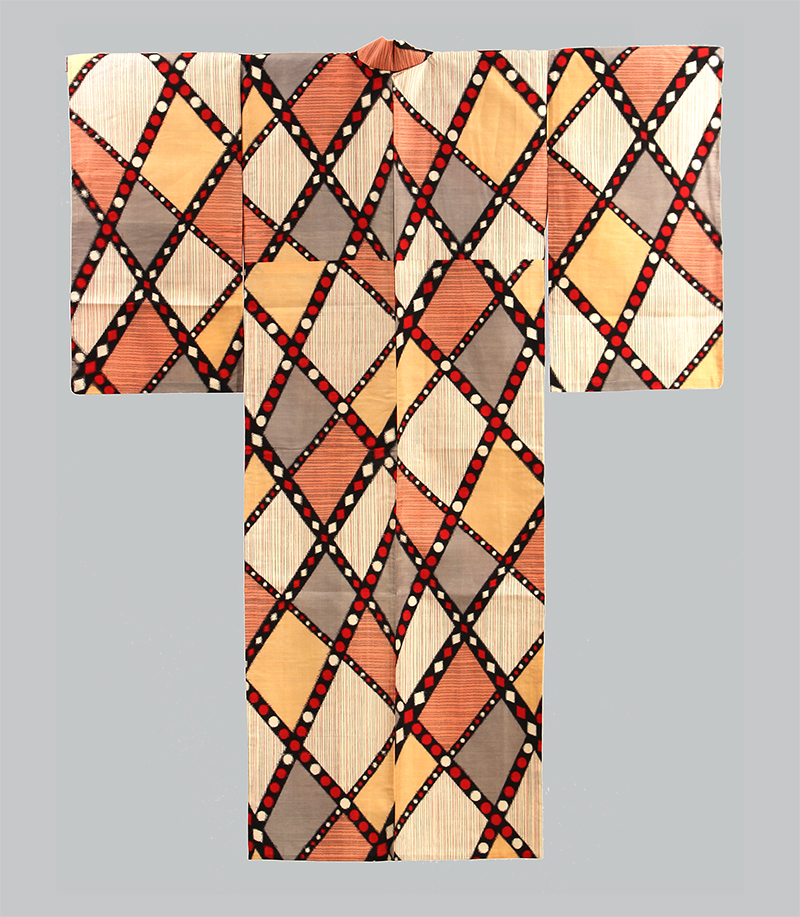

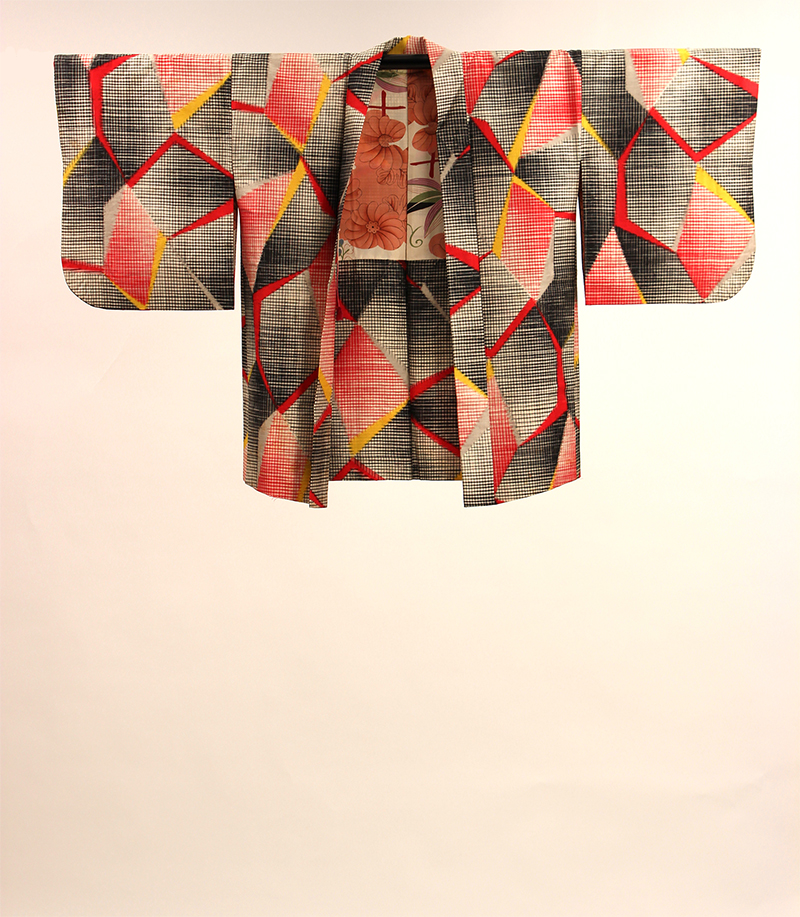

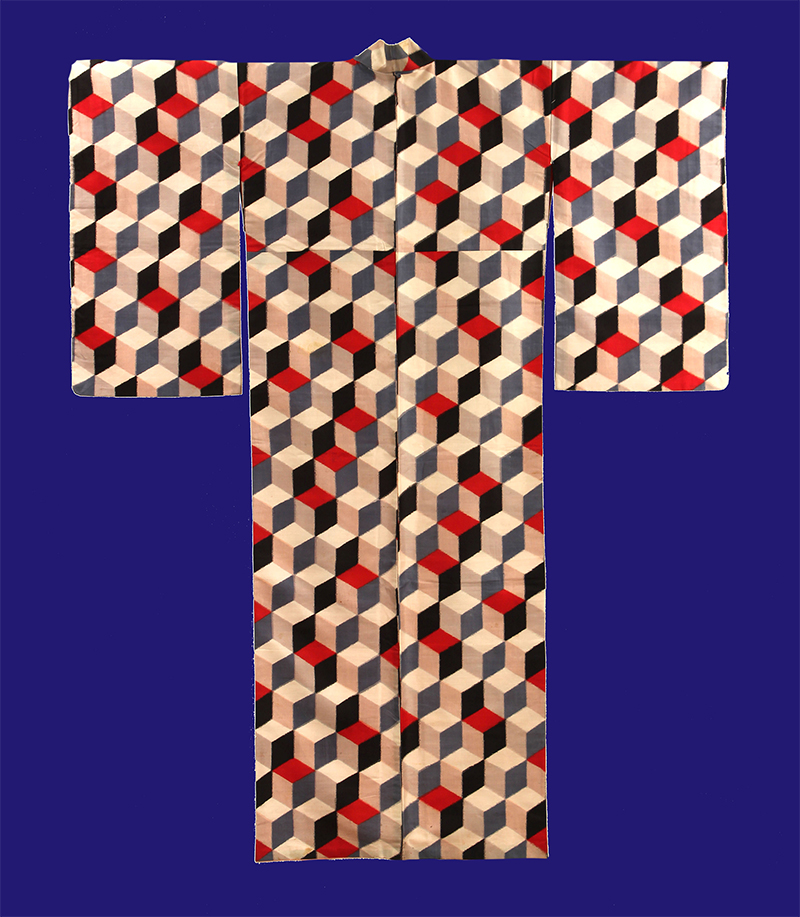

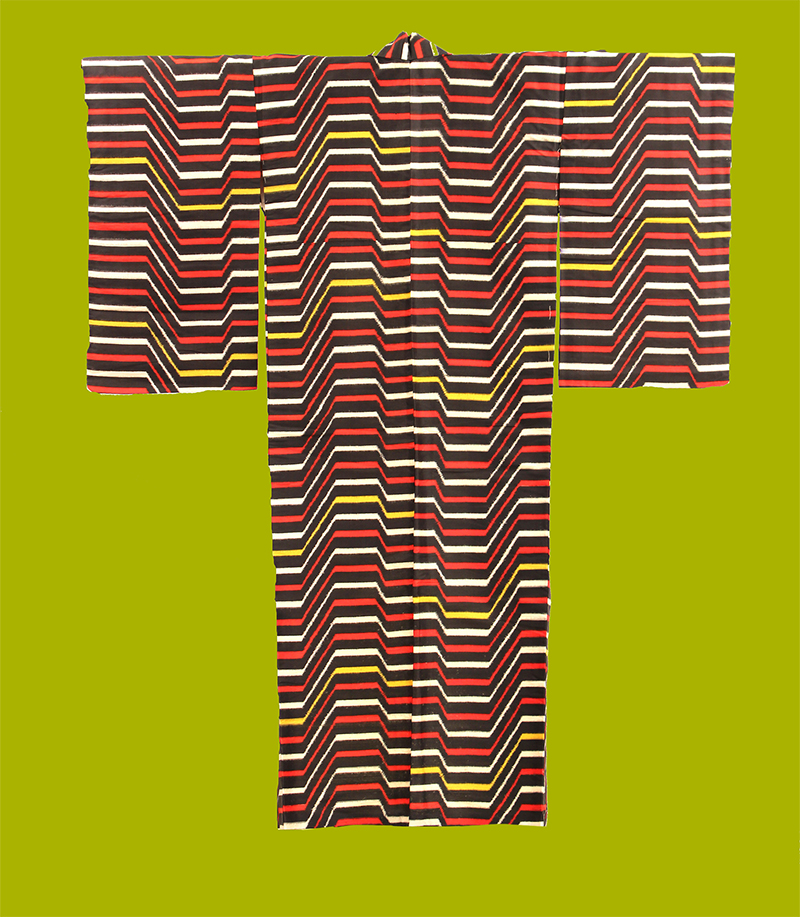

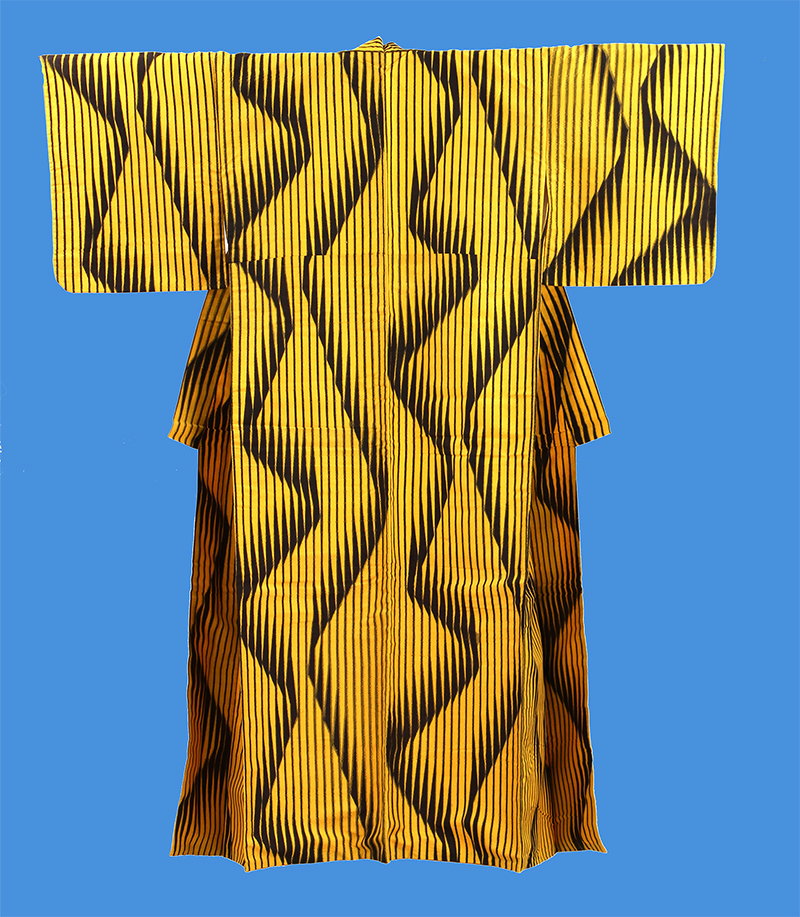

Meisen is a plain weave, hand-printed and woven silk textile, made popular between 1910 and 1950 in Japan. It was worn in kimono or haori form in everyday life by young women who embodied a new world order, marked by a desire for independence, education, and freedom. “ It is also said that woman who needed to look beautiful and stand out wore them, such as actresses, bar hostesses, and stage performers, those who were engaged in the entertainment business.”(1) The patterns found in the Meisen cloth are dazzling, bold, and largely abstract, reflecting the imaginative power in this time of dramatic social change. Most of the garments we see in the gallery were produced between 1930 and 1940 in the Gunma Prefecture of Japan. Nancy Price and Naoko Furue are pleased to present fifty-four of these outstanding pieces from the collection of Haruko Watanabe.

(1) Haruko Watanabe Kimono n.a thing to wear

The form comes out of the cloth. The kimono form is composed of rectangular surfaces cut selvedge to selvedge (thus creating no wastage), approximately 12 metres in length and 35 to 40 centimeters wide. Two long rectangular surfaces travel up the front and down the back, falling from each shoulder, forming the body of the garment. The sleeves are two panels of the same width sewn to the body at the shoulder. Two half-width panels are added to the front to allow for the crossover at the front. The garment wraps left side over right side and is held by a sash (obi). This transitional garment serves both sexes and is for the most part one size. It adjusts effortlessly in length by pulling and tucking the cloth. The body of the kimono always remains the same, however the sleeve styles change. The kimono is folded and stored in such as way as to occupy a minimal space and lie flat; it is easily deconstructed and reconstructed, and has the capacity to be worn through the course of one’s life. The fabric can be re-dyed to suit the changing age of the wearer.

Haruko Watanabe Collects This exhibition is comprised of fifty-four works from the collection of Ms. Watanabe, of Tokyo, Japan. She has collected Japanese, Chinese and European antiquities and vintage items since 1995. Her collections have included potteries, and boro (n.rag), kimono and furoshiki (n.wrapping cloth) Japanese textiles. Over the past six years an aspect of her collection practice has focused on the Meisen kimono. She exhibited her Meisen collection at L’Aiguille en F’ete in Paris, February 2014. She is a councillor at the Iwatate Folk Textile Museum in Tokyo. Ms. Watanabe’s passion is a direct response to the originality of the stunning, daring, and largely abstract compositions found in the Meisencloth. This response occurs in tandem with her interest in modernism and abstraction as seen in a variety of 20thcentury art and craft movements, specifically the Wiener Werkstatte, Russian Constructivism, Cubism, Art Nouveau and Art Deco. Through her research Ms. Watanabe correlates specific stylistic parallels between modern works of art and craft, and the explosion of imageries embedded in the perpendicular woven intersections of the Meisen cloth. In addition to this East/West mix, Ms.Watanabe recognized that other sources for the Meisen visual aesthetic are zoomed-in versions of traditional Japanese patterns such as yabane (plume), sayagata, ryusui (stream), Nami (wave), tsubodare (glaze dripping), karakusa (arabesque), yorokejima (vertical curves).

Historical Context In 1854 Japan “opened up” in response to one of several demands from the United States government. This resulted in dramatic changes in the social hierarchy with an aim at modernizing the country. This translated as an economic drive to increase production through industry, moving from an exchange, in-kind society to a cash-based society. At this time, during the Meiji period, silk was Japan’s biggest export. Japan participated in several world expositions: in Vienna 1873, Philadelphia 1876, Paris 1878,1889 and 1890, and Chicago 1893. This led to various East/West intersections and exchanges. The Art Nouveau Movement in Europe and America was highly influenced by this exposure to Eastern aesthetics and subject matter. Art Nouveau now looked to the natural world for inspiration, and the “power of Japanese line, the force of its rhythm and its accents, to arouse and influence us.” (2) The textile artisans lost their samurai based patrons and many of their products were no longer needed. Traditional kimono designs were primarily “ka-cho-fu-getsu” flowers, birds, wind and moon, symbolizing the beauty of nature. In 1885 chemical dying was combined with traditional paste-resist techniques. Kata-yuzen (direct stencil) dyeing was introduced as a new technique. (2) Henry Van de Velde 1910 Japonism in Western Painting from Whistler to Matisse Cambridge University Press

Meisen (pronounced, “may-sen”) Meisen silk fabric emerged in the 1880s and really prevailed between 1910 and 1950 in Japan. The Meisentextile was viewed as casual every-day attire, in addition to being fashionable, inexpensive, and durable. Meisen textiles were made from a less expensive pongee (non-continuous single filaments) silk fabric. Kato Jizaemon discovered that by sizing raw, degummed silk threads with soybean milk before dyeing, deeper and more brilliant colors could be obtained. The sizing made the silk more durable. The Meisen silk became bright, colorful, and bold with the use of chemical dyes. For the Meisentechnique, chemical dyes are mixed with rice paste (or another starch-based material) and applied to the surface of the threads. With the Meisentechnique the dye is applied to the warp and/or weft threads prior to weaving, rather than onto the surface of cloth. The threads are put onto a loom and loosely woven with a temporary thread (tane-ito), which holds the threads in place. After transferring this to a print table, chemical dyes are mixed with rice paste and applied with paper stencils, each colour using a different stencil. Then the dyed threads are put on the loom and woven. Because of the weaving process the threads shift and the imagery appears somewhat blurred around the edges similar to kasuri(ikat) technique. Meisenis sometimes classified as a type of kasuriand called kasuri-meisen. Initially only the warp threads were printed but eventually a method for stencil-printing the weft threads (yokoso-kasuri) was developed. Finally it could be applied to both the warp and the weft (heiyo-kasuri). The dramatic expression of these kimonos marked a distinct change. Young women wanted to be seen, rather than blend in. This Meisen technique revolutionized Japanese kimono fashion and was a direct challenge to traditional authority. The modern Japanese women, was interested in freedom and participation in education, culture, paid employment, public life, and citizenship. As in other parts of the world, these courageous women took risks in an effort to change the imbalance of power.

(1) Haruko Watanabe Kimono n.a thing to wear

The form comes out of the cloth. The kimono form is composed of rectangular surfaces cut selvedge to selvedge (thus creating no wastage), approximately 12 metres in length and 35 to 40 centimeters wide. Two long rectangular surfaces travel up the front and down the back, falling from each shoulder, forming the body of the garment. The sleeves are two panels of the same width sewn to the body at the shoulder. Two half-width panels are added to the front to allow for the crossover at the front. The garment wraps left side over right side and is held by a sash (obi). This transitional garment serves both sexes and is for the most part one size. It adjusts effortlessly in length by pulling and tucking the cloth. The body of the kimono always remains the same, however the sleeve styles change. The kimono is folded and stored in such as way as to occupy a minimal space and lie flat; it is easily deconstructed and reconstructed, and has the capacity to be worn through the course of one’s life. The fabric can be re-dyed to suit the changing age of the wearer.

Haruko Watanabe Collects This exhibition is comprised of fifty-four works from the collection of Ms. Watanabe, of Tokyo, Japan. She has collected Japanese, Chinese and European antiquities and vintage items since 1995. Her collections have included potteries, and boro (n.rag), kimono and furoshiki (n.wrapping cloth) Japanese textiles. Over the past six years an aspect of her collection practice has focused on the Meisen kimono. She exhibited her Meisen collection at L’Aiguille en F’ete in Paris, February 2014. She is a councillor at the Iwatate Folk Textile Museum in Tokyo. Ms. Watanabe’s passion is a direct response to the originality of the stunning, daring, and largely abstract compositions found in the Meisencloth. This response occurs in tandem with her interest in modernism and abstraction as seen in a variety of 20thcentury art and craft movements, specifically the Wiener Werkstatte, Russian Constructivism, Cubism, Art Nouveau and Art Deco. Through her research Ms. Watanabe correlates specific stylistic parallels between modern works of art and craft, and the explosion of imageries embedded in the perpendicular woven intersections of the Meisen cloth. In addition to this East/West mix, Ms.Watanabe recognized that other sources for the Meisen visual aesthetic are zoomed-in versions of traditional Japanese patterns such as yabane (plume), sayagata, ryusui (stream), Nami (wave), tsubodare (glaze dripping), karakusa (arabesque), yorokejima (vertical curves).

Historical Context In 1854 Japan “opened up” in response to one of several demands from the United States government. This resulted in dramatic changes in the social hierarchy with an aim at modernizing the country. This translated as an economic drive to increase production through industry, moving from an exchange, in-kind society to a cash-based society. At this time, during the Meiji period, silk was Japan’s biggest export. Japan participated in several world expositions: in Vienna 1873, Philadelphia 1876, Paris 1878,1889 and 1890, and Chicago 1893. This led to various East/West intersections and exchanges. The Art Nouveau Movement in Europe and America was highly influenced by this exposure to Eastern aesthetics and subject matter. Art Nouveau now looked to the natural world for inspiration, and the “power of Japanese line, the force of its rhythm and its accents, to arouse and influence us.” (2) The textile artisans lost their samurai based patrons and many of their products were no longer needed. Traditional kimono designs were primarily “ka-cho-fu-getsu” flowers, birds, wind and moon, symbolizing the beauty of nature. In 1885 chemical dying was combined with traditional paste-resist techniques. Kata-yuzen (direct stencil) dyeing was introduced as a new technique. (2) Henry Van de Velde 1910 Japonism in Western Painting from Whistler to Matisse Cambridge University Press

Meisen (pronounced, “may-sen”) Meisen silk fabric emerged in the 1880s and really prevailed between 1910 and 1950 in Japan. The Meisentextile was viewed as casual every-day attire, in addition to being fashionable, inexpensive, and durable. Meisen textiles were made from a less expensive pongee (non-continuous single filaments) silk fabric. Kato Jizaemon discovered that by sizing raw, degummed silk threads with soybean milk before dyeing, deeper and more brilliant colors could be obtained. The sizing made the silk more durable. The Meisen silk became bright, colorful, and bold with the use of chemical dyes. For the Meisentechnique, chemical dyes are mixed with rice paste (or another starch-based material) and applied to the surface of the threads. With the Meisentechnique the dye is applied to the warp and/or weft threads prior to weaving, rather than onto the surface of cloth. The threads are put onto a loom and loosely woven with a temporary thread (tane-ito), which holds the threads in place. After transferring this to a print table, chemical dyes are mixed with rice paste and applied with paper stencils, each colour using a different stencil. Then the dyed threads are put on the loom and woven. Because of the weaving process the threads shift and the imagery appears somewhat blurred around the edges similar to kasuri(ikat) technique. Meisenis sometimes classified as a type of kasuriand called kasuri-meisen. Initially only the warp threads were printed but eventually a method for stencil-printing the weft threads (yokoso-kasuri) was developed. Finally it could be applied to both the warp and the weft (heiyo-kasuri). The dramatic expression of these kimonos marked a distinct change. Young women wanted to be seen, rather than blend in. This Meisen technique revolutionized Japanese kimono fashion and was a direct challenge to traditional authority. The modern Japanese women, was interested in freedom and participation in education, culture, paid employment, public life, and citizenship. As in other parts of the world, these courageous women took risks in an effort to change the imbalance of power.